| Biohistory journal, Autumn, 2006: Index > Creating the Biohistory Journal in an effort to combine knowledge and beauty |

| Creating the Biohistory Journal in an effort to combine knowledge and beauty |

|

|

|

That is a matter of intuition

Nakamura: Okada: Nakamura: Okada: |

Do you understand or not?

Okada: Nakamura: |

Science and art, more dead than alive

Okada: Nakamura: Okada: |

Expressing science in language

Nakamura: Okada: Nakamura: |

Expression in the original Japanese language

Okada: Nakamura: Okada: |

Entertainment is a major assignment

Nakamura: Okada: Nakamura: Okada: Nakamura: Nakamura: Okada: |

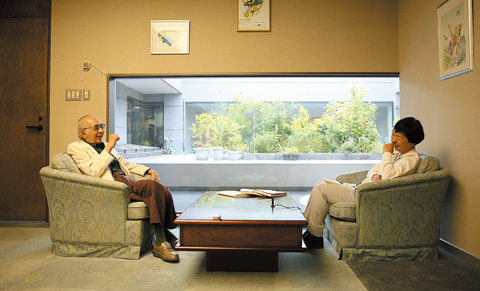

After the dialogue / Tokindo Okada

I donít like dialogues very much. Thereís not a whole lot I can do in these forums, which have been popular lately. People who are inhibited or shy by nature arenít suited for them. But it was a different matter altogether to have a dialogue with Ms. Nakamura to commemorate the 50th issue. At a minimum, there is a spirit of seeking a viewpoint different from what is currently popular or in the mainstream. By nature, I am a bit inhibited when it comes to talking or writing about such things. But I was glad to have this opportunity to talk a little about my state of mind now (typical of an old man), which I havenít spoken or written about before. The JT Biohistory Research Hall has an innate quietude. This is essentially different from the universities, research institutes, and museums that exist today. It is contrary to our essential nature to evaluate them as having no vitality. But there are festivals once or twice a year, and they are entirely suitable to the elegant atmosphere of this institute. Itís good that there is excitement. Tsutomu Ohashi |

| Dialogue |

Please close a window with the button of a browser who are turning off Javascript. |